Peter G. Moody is a Visiting Scholar at the Seoul National University Asia Center (SNUAC) from Columbia University status and will be defending his dissertation this semester. While researching his dissertation, Peter has served in various capacities such as a Visiting Research Fellow at the Institute for Far Eastern Studies, Kyungnam University, an Adjunct Professor at the University of Maryland at Baltimore County, and a research fellow with the US Fulbright Program. His research focuses on the historical development of North Korean culture and ideology, inter-Korean relations, and North Korea’s music diplomacy in East Asia. Peter’s academic work on North Korea has been featured in various peer-reviewed journals including Korean Studies, Korea Journal, Sungkyun Journal of East Asian Studies, and North Korean Review. He is currently in the early stages of a book manuscript entitled Mobilizing Musicians and the Making of North Korea.

Review

<From Liberation Space to Post-Liberation: The Lives and Activities of Two Early North Korean Musicians (1945-1953)>

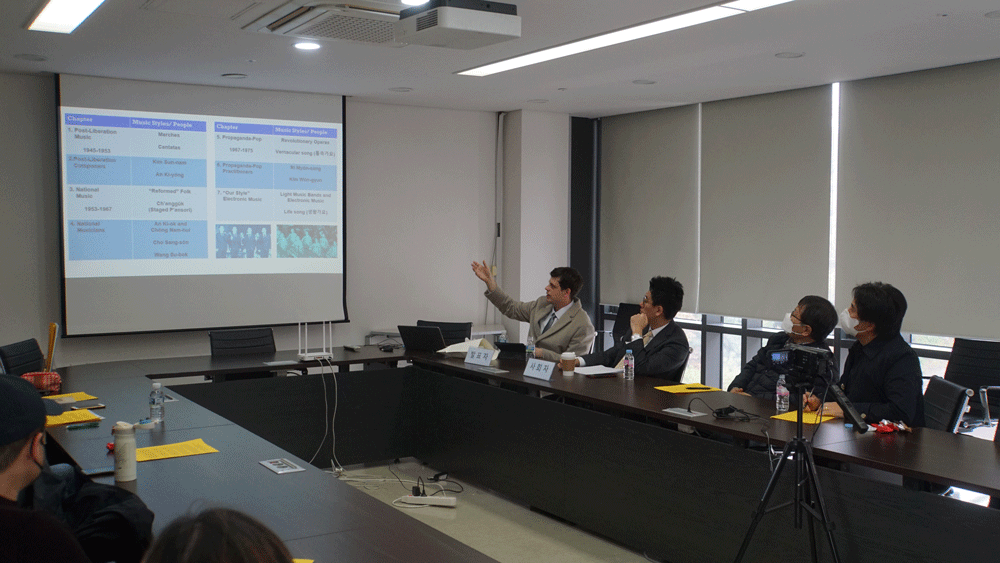

Speaker: Peter G. Moody (SNUAC)

Research on music can always be a useful and enriching way to analyze both the core cultural pillars and trends of a certain society. In particular, an observation of the history of North Korean musicians would reflect meaningful implications about the North Korean society itself, especially when considering the fact that North Korea and its short history remains relatively opaque to outsiders.

Today’s Brownbag Seminar was led by Peter G. Moody (Columbia University, Visiting Scholar at SNUAC), who deeply engaged with this topic of North Korean music history. By introducing the analytical concept of “post-liberation”, he attempted to go beyond dichotomous frameworks that had been dominantly applied to prior research on North Korean music; Does North Korean music preserve the indigenous music culture, or does it strive towards updates to meet international trends? Does it function as a weapon of revolution, or does it remain a companion for daily life? Instead of trying to capture North Korean music history through these monolithic, or bifurcated, perspectives, Dr. Moddy uses the concept of “post-liberation” to rather shifts the lenses to sharpen the understanding of different cultural productions made within the Korean peninsula accompanying the aftermath of the Japanese surrender.

Dr. Moody also mentioned that the concept of the “post-liberation” space was introduced as a means to critically supplement the more commonly used concept of a “liberation space”. He argues that this prior term does not capture the retained features of liberation which Korean musicians tended to present even during the initial stages of North-South division. So instead of delimiting the concept of liberation as a mere periodical marker (1945-1953), Dr. Moody uses the term “post-liberation” not only to indicate a periodical extension of the Korean “liberation space”, but also as a way to shed light on the new forms of agency and dynamic endeavors that the artists pursued even as their de jure liberated status became compromised after 1950.

Dr. Moody particularly focuses on the lives of two Korean musicians who were both born in the South but would later migrate to the North. First, Kim Sun-nam (김순남) is known to have been a leading cultural figure after his move to North Korea, composing several liberation songs during the period of the “liberation space”. While his ideological inclination towards Korean nationalism and leftist movements blossomed, he was also one of the first musicians to exhibit modernist techniques while at the same time holding national music concerts that included Korean folk songs. However, due to the North Korean government’s ongoing suspicion about his political stance, Kim Sun-nam has been criticized for his lack of demonstrating a real ‘conversion’ to communism. As a result, Kim Sun-nam’s pieces have rarely been mentioned in North Korean texts.

An Ki-yong (안기영) was also a musician who moved to North Korea and became an influential figure, shaping the artistic development and institutional practices of DPRK musical establishment. In contrast to Kim Sun-nam, whose musical pieces focused more on compositional mastery and self-expression, An Ki-yong was more passionate about adapting Korean folk songs to modern (Western) tones. He considered Korean folk songs as “pearls buried in mud”, and contributed to rediscovering indigenous Korean music into contemporary music trends that had been introduced from the West.

While Kim Sun-nam and Ah Ki-yong’s life and journey as a Korean musician can be compared and contrasted from different angles, Dr. Moody notes an analogous form of “subservient nationalism” that is commonly displayed in both lives, even after the North-South division of Korea. The musical works of both men presented, at least temporarily, means of affirming and strengthening their identities to Koreans while also pursuing their individual aims. Thus, the concept of a “post-liberation” space sheds light on the new forms of agency that the two musicians had demonstrated, which cannot be dynamically comprehended through the former “liberation space” demarcation.

[아시아연구소 연구연수생 17기 학술기자단 김호수]